Chapter 5 Section 5.6: The Doppler Effect

5.6 The Doppler Effect

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain why the spectral lines of photons we observe from an object will change as a result of the object’s motion toward or away from us

- Describe how we can use the Doppler effect to deduce how fast astronomical objects are moving through space

The last two sections introduced you to many new concepts, and we hope that through those, you have seen one major idea emerge. Astronomers can learn about the elements in stars and galaxies by decoding the information in their spectral lines. There is a complicating factor in learning how to decode the message of starlight, however. If a star is moving toward or away from us, its lines will be in a slightly different place in the spectrum from where they would be in a star at rest. And most objects in the universe do have some motion relative to the Sun.

Motion Affects Waves

In 1842, Christian Doppler first measured the effect of motion on waves by hiring a group of musicians to play on an open railroad car as it was moving along the track. He then applied what he learned to all waves, including light, and pointed out that if a light source is approaching or receding from the observer, the light waves will be, respectively, crowded more closely together or spread out. The general principle, now known as the Doppler effect, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Doppler Effect.

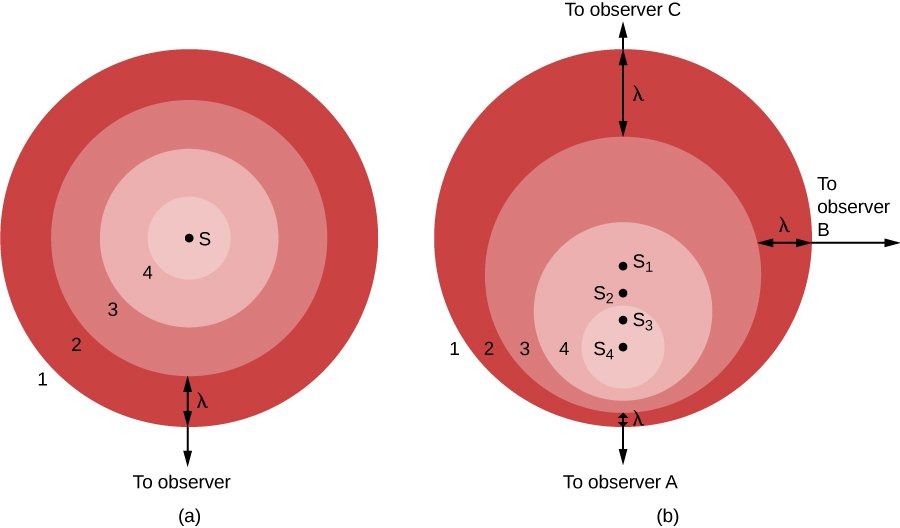

Figure 1. (a) A source, S, makes waves whose numbered crests (1, 2, 3, and 4) wash over a stationary observer. (b) The source S now moves toward observer A and away from observer C. Wave crest 1 was emitted when the source was at position S1, crest 2 at position S2, and so forth. Observer A sees waves compressed by this motion and sees a blueshift (if the waves are light). Observer C sees the waves stretched out by the motion and sees a redshift. Observer B, whose line of sight is perpendicular to the source’s motion, sees no change in the waves (and feels left out).

Figure 1. (a) A source, S, makes waves whose numbered crests (1, 2, 3, and 4) wash over a stationary observer. (b) The source S now moves toward observer A and away from observer C. Wave crest 1 was emitted when the source was at position S1, crest 2 at position S2, and so forth. Observer A sees waves compressed by this motion and sees a blueshift (if the waves are light). Observer C sees the waves stretched out by the motion and sees a redshift. Observer B, whose line of sight is perpendicular to the source’s motion, sees no change in the waves (and feels left out).

In part (a) of the figure, the light source (S) is at rest with respect to the observer. The source gives off a series of waves, whose crests we have labeled 1, 2, 3, and 4. The light waves spread out evenly in all directions, like the ripples from a splash in a pond. The crests are separated by a distance, λ, where λ is the wavelength. The observer, who happens to be located in the direction of the bottom of the image, sees the light waves coming nice and evenly, one wavelength apart. Observers located anywhere else would see the same thing.

On the other hand, if the source of light is moving with respect to the observer, as seen in part (b), the situation is more complicated. Between the time one crest is emitted and the next one is ready to come out, the source has moved a bit, toward the bottom of the page. From the point of view of observer A, this motion of the source has decreased the distance between crests—it’s squeezing the crests together, this observer might say.

In part (b), we show the situation from the perspective of three observers. The source is seen in four positions, S1, S2, S3, and S4, each corresponding to the emission of one wave crest. To observer A, the waves seem to follow one another more closely, at a decreased wavelength and thus increased frequency. (Remember, all light waves travel at the speed of light through empty space, no matter what. This means that motion cannot affect the speed, but only the wavelength and the frequency. As the wavelength decreases, the frequency must increase. If the waves are shorter, more will be able to move by during each second.)

The situation is not the same for other observers. Let’s look at the situation from the point of view of observer C, located opposite observer A in the figure. For her, the source is moving away from her location. As a result, the waves are not squeezed together but instead are spread out by the motion of the source. The crests arrive with an increased wavelength and decreased frequency. To observer B, in a direction at right angles to the motion of the source, no effect is observed. The wavelength and frequency remain the same as they were in part (a) of the figure.

We can see from this illustration that the Doppler effect is produced only by a motion toward or away from the observer, a motion called radial velocity. Sideways motion does not produce such an effect. Observers between A and B would observe some shortening of the light waves for that part of the motion of the source that is along their line of sight. Observers between B and C would observe lengthening of the light waves that are along their line of sight.

You may have heard the Doppler effect with sound waves. When a train whistle or police siren approaches you and then moves away, you will notice a decrease in the pitch (which is how human senses interpret sound wave frequency) of the sound waves. Compared to the waves at rest, they have changed from slightly more frequent when coming toward you, to slightly less frequent when moving away from you.

Color Shifts

When the source of waves moves toward you, the wavelength decreases a bit. If the waves involved are visible light, then the colors of the light change slightly. As wavelength decreases, they shift toward the blue end of the spectrum: astronomers call this a blueshift (since the end of the spectrum is really violet, the term should probably be violetshift, but blue is a more common color). When the source moves away from you and the wavelength gets longer, we call the change in colors a redshift. Because the Doppler effect was first used with visible light in astronomy, the terms “blueshift” and “redshift” became well established. Today, astronomers use these words to describe changes in the wavelengths of radio waves or X-rays as comfortably as they use them to describe changes in visible light.

The greater the motion toward or away from us, the greater the Doppler shift. If the relative motion is entirely along the line of sight, the formula for the Doppler shift of light is

where λ is the wavelength emitted by the source, Δλ is the difference between λ and the wavelength measured by the observer, c is the speed of light, and v is the relative speed of the observer and the source in the line of sight. The variable v is counted as positive if the velocity is one of recession, and negative if it is one of approach. Solving this equation for the velocity, we find v = c × Δλ/λ.

If a star approaches or recedes from us, the wavelengths of light in its continuous spectrum appear shortened or lengthened, respectively, as do those of the dark lines. However, unless its speed is tens of thousands of kilometers per second, the star does not appear noticeably bluer or redder than normal. The Doppler shift is thus not easily detected in a continuous spectrum and cannot be measured accurately in such a spectrum. The wavelengths of the absorption lines can be measured accurately, however, and their Doppler shift is relatively simple to detect.

The Doppler Effect

We can use the Doppler effect equation to calculate the radial velocity of an object if we know three things: the speed of light, the original (unshifted) wavelength of the light emitted, and the difference between the wavelength of the emitted light and the wavelength we observe. For particular absorption or emission lines, we usually know exactly what wavelength the line has in our laboratories on Earth, where the source of light is not moving. We can measure the new wavelength with our instruments at the telescope, and so we know the difference in wavelength due to Doppler shifting. Since the speed of light is a universal constant, we can then calculate the radial velocity of the star.A particular emission line of hydrogen is originally emitted with a wavelength of 656.3 nm from a gas cloud. At our telescope, we observe the wavelength of the emission line to be 656.6 nm. How fast is this gas cloud moving toward or away from Earth?

Solution

Because the light is shifted to a longer wavelength (redshifted), we know this gas cloud is moving away from us. The speed can be calculated using the Doppler shift formula:

Check Your Learning

Suppose a spectral line of hydrogen, normally at 500 nm, is observed in the spectrum of a star to be at 500.1 nm. How fast is the star moving toward or away from Earth?

ANSWER:

Because the light is shifted to a longer wavelength, the star is moving away from us:

![]()

Its speed is 60,000 m/s.

You may now be asking: if all the stars are moving and motion changes the wavelength of each spectral line, won’t this be a disaster for astronomers trying to figure out what elements are present in the stars? After all, it is the precise wavelength (or color) that tells astronomers which lines belong to which element. And we first measure these wavelengths in containers of gas in our laboratories, which are not moving. If every line in a star’s spectrum is now shifted by its motion to a different wavelength (color), how can we be sure which lines and which elements we are looking at in a star whose speed we do not know?

Take heart. This situation sounds worse than it really is. Astronomers rarely judge the presence of an element in an astronomical object by a single line. It is the pattern of lines unique to hydrogen or calcium that enables us to determine that those elements are part of the star or galaxy we are observing. The Doppler effect does not change the pattern of lines from a given element—it only shifts the whole pattern slightly toward redder or bluer wavelengths. The shifted pattern is still quite easy to recognize. Best of all, when we do recognize a familiar element’s pattern, we get a bonus: the amount the pattern is shifted can enable us to determine the speed of the objects in our line of sight.

The training of astronomers includes much work on learning to decode light (and other electromagnetic radiation). A skillful “decoder” can learn the temperature of a star, what elements are in it, and even its speed in a direction toward us or away from us. That’s really an impressive amount of information for stars that are light-years away.

Key Concepts and Summary

If an atom is moving toward us when an electron changes orbits and produces a spectral line, we see that line shifted slightly toward the blue of its normal wavelength in a spectrum. If the atom is moving away, we see the line shifted toward the red. This shift is known as the Doppler effect and can be used to measure the radial velocities of distant objects.

For Further Exploration

Articles

Augensen, H. & Woodbury, J. “The Electromagnetic Spectrum.” Astronomy (June 1982): 6.Darling, D. “Spectral Visions: The Long Wavelengths.” Astronomy (August 1984): 16; “The Short Wavelengths.” Astronomy (September 1984): 14.Gingerich, O. “Unlocking the Chemical Secrets of the Cosmos.” Sky & Telescope (July 1981): 13.Stencil, R. et al. “Astronomical Spectroscopy.” Astronomy (June 1978): 6.

Websites

Doppler Effect: http://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/waves/Lesson-3/The-Doppler-Effect. A shaking bug and the Doppler Effect explained.

Electromagnetic Spectrum: http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/science/toolbox/emspectrum1.html. An introduction to the electromagnetic spectrum from NASA’s Imagine the Universe; note that you can click the “Advanced” button near the top and get a more detailed discussion.

Rainbows: How They Form and How to See Them: http://www.livescience.com/30235-rainbows-formation-explainer.html. By meteorologist and amateur astronomer Joe Rao.

Videos

Doppler Effect: http://www.esa.int/spaceinvideos/Videos/2014/07/Doppler_effect_-_classroom_demonstration_video_VP05. ESA video with Doppler ball demonstration and Doppler effect and satellites (4:48).

How a Prism Works to Make Rainbow Colors: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JGqsi_LDUn0. Short video on how a prism bends light to make a rainbow of colors (2:44).

Tour of the Electromagnetic Spectrum: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPcAWNlVl-8. NASA Mission Science video tour of the bands of the electromagnetic spectrum (eight short videos).

Introductions to Quantum Mechanics

Ford, Kenneth. The Quantum World. 2004. A well-written recent introduction by a physicist/educator.

Gribbin, John. In Search of Schroedinger’s Cat. 1984. Clear, very basic introduction to the fundamental ideas of quantum mechanics, by a British physicist and science writer.

Rae, Alastair. Quantum Physics: A Beginner’s Guide. 2005. Widely praised introduction by a British physicist.

Collaborative Group Activities

- Have your group make a list of all the electromagnetic wave technology you use during a typical day.

- How many applications of the Doppler effect can your group think of in everyday life? For example, why would the highway patrol find it useful?

- Have members of your group go home and “read” the face of your radio set and then compare notes. If you do not have a radio, research “broadcast radio frequencies” to find answers to the following questions. What do all the words and symbols mean? What frequencies can your radio tune to? What is the frequency of your favorite radio station? What is its wavelength?

- If your instructor were to give you a spectrometer, what kind of spectra does your group think you would see from each of the following: (1) a household lightbulb, (2) the Sun, (3) the “neon lights of Broadway,” (4) an ordinary household flashlight, and (5) a streetlight on a busy shopping street?

- Suppose astronomers want to send a message to an alien civilization that is living on a planet with an atmosphere very similar to that of Earth’s. This message must travel through space, make it through the other planet’s atmosphere, and be noticeable to the residents of that planet. Have your group discuss what band of the electromagnetic spectrum might be best for this message and why. (Some people, including noted physicist Stephen Hawking, have warned scientists not to send such messages and reveal the presence of our civilization to a possible hostile cosmos. Do you agree with this concern?)

Review Questions

Thought Questions

With what type of electromagnetic radiation would you observe:

- A star with a temperature of 5800 K?

- A gas heated to a temperature of one million K?

- A person on a dark night?

Figuring for Yourself

Glossary

- Doppler effect

- the apparent change in wavelength or frequency of the radiation from a source due to its relative motion away from or toward the observer

- radial velocity

- motion toward or away from the observer; the component of relative velocity that lies in the line of sight